Safety Systems Need Diverse Voices to be their Best

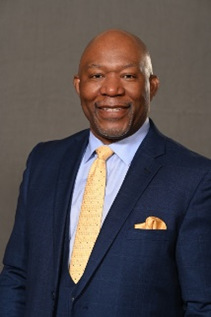

Contribution by Dr. I. David Daniels, CSD, VPS

Black History in Canada

Before Mathieu Da Costa’s visit in the early 17th century, there was no particular reason to be concerned about a black person, as he was the first to visit Canada. According to the Government of Canada, “The role of Black Canadians and their communities in Canada has largely been ignored as a key part of Canada’s history.” The House of Commons recognized February as Black History Month in December 1995. However, it was not until February 2008 that the parliamentary position on establishing Black History Month was completed as the result of the introduction of the Motion to Recognize Contributions of Black Canadians and February as Black History Month. Senator Donald Oliver, the first black person to serve in the Canadian Senate, introduced this motion. At the time of this motion’s passing, there was only one other black member of the Senate, or 1.9% of the total.

While one could argue that lack of interest in a holiday is hardly evidence of hostility toward black people by the remainder of the Canadian House of Commons and Senate, the perception of black workers in federal service was different. In December 2020, a class action lawsuit in the amount of 2.5 billion dollars was filed with the United Nations on behalf of 45,000 black workers alleging racism, discrimination, and exclusion. The complaint suggests that attempts to address these concerns have failed to address the problem and exacerbated systemic inequalities.

While homogeneity is not inherently negative or the product of overtly ill intent, it is “the state or quality of being homogeneous, consisting of parts or elements that are all the same.” The presence of homogeneity inevitably results in the lack of diverse views, voices, and perspectives and is often the underlying driver behind a lack of psychological safety. A group that feels, thinks, and acts similarly is likely to resist new ways of feeling, thinking, or acting out of the natural tendency toward self-protection.

One of the products of having Black History Month is that it brings to the forefront conversations about racism and discrimination in a country that many, both inside and outside the country, believe doesn’t have an issue with either. In the aftermath of George Floyd’s killing by police in the United States, several public figures commented on the absence of systemic racism in Canada. This form of denial is a part of the construct that many would describe as systemic racism. There are these myths that we are so radically different from the US.

Canada is a multicultural country, both socially and legally. From a policy perspective, multiculturalism has several goals, including recognizing and promoting the racial and cultural diversity of Canadian society while emphasizing that this is a fundamental characteristic of Canadian identity and heritage, promoting equal participation of individuals and communities in Canadian society, and assisting in the elimination of barriers to participation; and ensuring that individuals receive equal treatment and equal protection under the law while respecting and valuing their diversity, among several others.

When is Racism Considered Systemic

Racism is the relegation of people of color to inferior status and treatment based on unfounded beliefs about innate inferiority and unjust treatment and oppression of people of color, whether intended or not. Racism is not always conscious, intentional, or explicit—often, it is systemic and structural. Systemic racism is an interconnecting and shared relationship between individuals, institutions, and structures that function as a system of racism that exists on three levels. These various levels of racism operate together in a lockstep model and function together as a whole system:

- Individual (within interactions between people) racism. Structured by an ideology (set of ideas, values, and beliefs) that frames one's adverse feelings towards others; and is reflected in the willful, conscious/unconscious, direct/indirect, or intentional/unintentional words or actions of individuals.

- Institutional (within institutions and systems of power) racism. It exists in organizations or institutions where the established rules, policies, and regulations are informed by and inform the institutions' norms, values, and principles. These, in turn, methodically produce a disparity of treatment or discriminatory practices towards various groups based on race. Individuals enact it within organizations that accept and administer these rules, policies, and regulations because of their socialization, training, and loyalty to the organization. It maintains a system of social control that favors the dominant cultural groups (status quo).

- Structural or societal (among institutional and across society) racism. Pertains to the ideologies upon which society is structured. These ideologies are inscribed through rules, policies, and laws; and represent how the deep-rooted inequities of society produce differentiation, categorization, and stratification of society's members based on race. Participation in economic, political, social, cultural, judicial, and educational institutions also structures this stratification.

In 2017, at the start of the XXI World Congress on Safety and Health at Work, representatives of business and workers, education institutions, policy-makers in governments and public authorities, OHS professional organizations, and experts in occupational health and safety (OHS) joined the International Network of Safety and Health Practitioner Organizations (INSHPO) and its members to sign the Singapore Accord (pictured above), a commitment to improving OHS professional and practitioner capabilities so they may more effectively guide and lead the creation of healthier and safer workplaces.

Signatories to the accord agreed regarding:

- Commitment to improving OHS professional and practitioner capabilities so they may more effectively guide and lead the creation of healthier and safer workplaces.

- Commitment to promoting the use and acceptance of the Framework as a common platform to develop capable, knowledgeable, and skilled OHS professionals and practitioners across industry sectors and geographic borders.

- Commitment to striving to use the Framework to inform our work about improving the competence and capability of the profession and, thereby, occupational health and safety standards across the world:

- As OHS professionals and practitioners – as a reference and basis for gap analysis about our professional practice and career development, to aid the development of continuing professional development plans to ensure that we are capable;

- As OHS member associations – in the development of professional educational programs and as a benchmark to ensure that our members possess relevant and up‐to‐date skills which allow them to undertake their roles competently and effectively;

- As OHS certification bodies and credentialing organizations – as a resource in the development of our certification standards and designations and other assessment processes;

- As employers and human resource professionals – in developing position descriptions for OHS roles, in recruiting OHS personnel, and in performance evaluation as a basis for professional development;

- As OHS educators – in developing and reviewing OHS education programs;

- As policymakers in governments and public authorities – in developing legislation or regulations that govern competent or reliable OHS advice or the role and development of OHS practitioners and professionals at workplaces.

- Commitment to continued cooperation and collaboration in developing global standards of practice to improve the skills and capability of OHS professionals and practitioners and adapt the Framework to meet the needs of key stakeholders around the world.

Why it Matters

Given that racism is “not always conscious, intentional, or explicit,” individuals involved in developing and implementing any system, policies, procedures, and practices associated with the system may unconsciously and unintentionally reflect their biases through their actions. Institutions rely on the expertise, involvement, and support of individuals who can not or do not separate from those biases. Structures reinforce those biases and produce outcomes that benefit those involved in their design. Once these structures and systems are in place, they may not benefit those not included in their design. To open these processes to new increase their effectiveness for broader audiences will require involvement from broader audiences. So, after reading this article this far, you may ask, “what does this information have to do with safety,” particularly, what does it have to do with credentialing? Additionally, why is this important during Black History Month?

The value and applicability of a system to evaluate the effectiveness of a safety management system and the role that human beings play in the system are predicated on the diversity of thoughts of those that develop the system itself. This is not to suggest that the input from a homogeneous group is horrible; it is to suggest that it is incomplete. A significant body of data suggests that women's exposure, injury, and fatality rates are generally higher than other workers in virtually every industry and occupation. Additionally, occupational safety and health, as well as almost every other safety-focused industry, was researched, imagined, established, organized, and validated by homogeneous groups. Again, this is not to suggest that these systems are ineffective; they are, however, less effective for those not involved in the design of the systems themselves. Any component of a safety management system not designed to identify, assess, and mitigate hazards while also decreasing vulnerability for ALL of those exposed to the remaining hazards is a system that will never be all it can be.

In 2021, a new organization called the Canadian Association for Black Health, and Safety Professionals (CABHSP) was created. The organization is focused on creating a more diverse, equitable, and inclusive occupational safety industry in Canada and improving the opportunities for black safety professionals to engage in the profession. The association’s membership represents a spectrum of private and public sector industries. The members also share several other experiences, including situations where their exceptional credibility, capability, and capacity to serve as health and safety professionals have been questioned, challenged, underestimated, and underutilized. The CABHSP could be an excellent option for national and global safety communities to diversify their standard-making and credential-granting processes to ensure more voices are involved. The CABHSP is thrilled that the Singapore Accord exists and would offer its members their expertise and diverse experience to strengthen health and safety standards.

About the Author:

Dr. I. David Daniels is a senior advisor for the Canadian Association for Black Health and Safety Professionals. He is an occupational health and safety professional, thought leader, former Fire Chief, and President/CEO of ID2 Solutions, LLC. Dr. Daniels holds a Ph.D. in Occupational Health and Safety and a Master’s degree in Human Resource Management. He is certified as a Safety Director, Violence Prevention Specialist, Emergency Management Specialist, Safety and Health Specialist, and certified in Mental Health First Aid. Dr. Daniels serves as a member of the National Safety Council (NSC) Board of Directors and is the recipient of NSC’s highest honor, the Distinguished Service to Safety Award. He’s also chair of the National Association of Black Compliance and Risk Management Professionals Safety and Security Workgroup.

References

Ref1 Government of Canada. (n.d.). About Black History Month. Retrieved from https://www.canada.ca/en/canadian-heritage/campaigns/black-history-month/about.html on January 17, 2023.

Ref2 Dictionary.com. (2023). Homogeneity. Retrieved on January 17, 2023, from https://www.dictionary.com/browse/homogeneity.

Ref3 Statistics Canada. (n.d.) Experiences of discrimination among the Black and Indigenous populations in Canada, 2019. Retrieved on January 18, 2023, from https://www150.statcan.gc.ca/n1/pub/85-002-x/2022001/article/00002-eng.htm

Ref4 Government of Canada (n.d.). Racial Discrimination and Migrant Workers in Canada: Evidence from the Literature. Retrieved on January 18, 2023, from https://www.canada.ca/en/immigration-refugees-citizenship/corporate/reports-statistics/research/racism-discrimination-migrant-workers-canada-evidence-literature.html#s

Ref5 Jones, C. (2000). Levels of racism: a theoretic framework and a gardener’s tale. Am J Public Health; 90(8):1212–5.